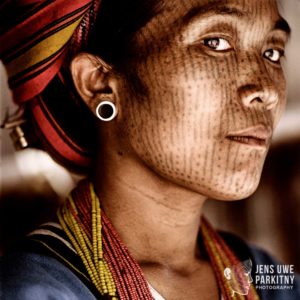

Jens Uwe Parkitny

A last glimpse of a vanishing tradition of body adornment in the Mekong Region

The Laven people in Laos, the Brau people in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia as well as the Dulong people in Yunnan Province in China used to do it for many centuries: tattooing the faces of their young girls once they reached puberty. Only a few elders of these ethnic minorities still bear the ancient marks of their ancestors. The practice of female facial tattooing among the different hill tribes in the Mekong region, however, was once fairly widespread.

Today, Myanmar is home to the largest group of traditionally face-tattooed women in Asia: the women of the Southern Chin. In the remote villages of Western Myanmar, located on the mountain slopes of Chin State and along the banks of the Lemro River that meanders through Chin and Rakhine states, the custom of facial tattooing survived until fairly recently.

Today, Myanmar is home to the largest group of traditionally face-tattooed women in Asia: the women of the Southern Chin. In the remote villages of Western Myanmar, located on the mountain slopes of Chin State and along the banks of the Lemro River that meanders through Chin and Rakhine states, the custom of facial tattooing survived until fairly recently.

The last confirmed traditional facial tattooing session of a Chin girl took place twenty-one years ago in a remote village in Myebone Township, Rakhine State. The Chin girl, Khin Htay, was 12-years-old when the intricate tattoo patterns of her group were applied to her forehead, cheeks, nose, chin and eye lids, marking her as a Laytu Chin.

This is quite remarkable considering facial tattooing in Myanmar had been banned on the basis of “health concerns” by the Union Revolutionary Council, the supreme governing body of Burma from 1962-1974. This ban was never lifted.

In remote areas, however, tattooing continued to be practiced by Chin communities until 2000. The remoteness preserved this ancient tradition and even the long arm of the government was not able to reach these far-flung settlements.

Why did the custom begin in the first place?

Why did the custom begin in the first place?

“To make themselves unattractive to outside intruders”, is the most common explanation. The story goes that Burmese kings sent their soldiers to the Chin Mountains to abduct Chin girls, who were renowned for their beauty, and to enslave them as court mistresses.

In order to stop the abductions, Chin communities started to “mark” the faces of the young girls, once they reached puberty. Using rattan thorns, symbols and patterns were “tapped” into the dermal tissues of the face and rubbed with a mixture made of soot, water and creeper plant sap to create permanent marks that deliberately destroyed their beautiful appearance. The king lost interest and his men were never seen again in the villages. The tattoo tradition, however, lived on.

This story though, is a myth. Historically, there is no evidence that any of the kings of Myanmar systematically raided Chin villages in the plains or in the mountains.

The reason for facial tattooing among the Chin, and other hill tribes, is complex, and was certainly not done to deface the women in order to protect them from any form of slavery or abduction.

The reason for facial tattooing among the Chin, and other hill tribes, is complex, and was certainly not done to deface the women in order to protect them from any form of slavery or abduction.

All cultures, that practiced or still practice facial tattooing in one form or the other, perceive it as beautiful and elevates the status of the person tattooed rather than defacing them, writes Dr. Lars Krutak, a world leading tattoo anthropologist (Krutak, 2007).

The tradition of female facial marking, is only found among those Chin groups that settle in the Southern parts of Chin State, in Western Rakhine, particular along the Lemro River, and in the neighboring areas of the Magway Administrative Division. Neither the groups in the North of Chin State nor those that live in Bangladesh (where they are called “Zo”) or India practice the custom.

Each facial tattoo pattern among the different Chin groups – and other ethnics that practiced this form of body adornment such as the Dulong, the Laven and the Brau – is a visual expression of belonging and identity. It marks the ability to endure pain, of having mastered different stages in live, of being a full member of the community with duties, privileges and status, of a particular beauty perception and – last not least – of a certain spiritual and super-natural believe.

A facial tattoo is like a permanent mask and, while ritually applied, this mask is super-charged with protective charms that are meant to fend off evil spirits, in life – and maybe even in the afterlife. (Krutak 2007; 2012). Some groups of the Naga, linguistically related to the Chin, for instance believe that their ancestors cannot recognize them if they do not bear the ancient tattoo marks on their face and forehead (Saul, 2005). It is therefore possible that some of the Chin and other groups in the Mekong region followed a similar believe.

A facial tattoo is like a permanent mask and, while ritually applied, this mask is super-charged with protective charms that are meant to fend off evil spirits, in life – and maybe even in the afterlife. (Krutak 2007; 2012). Some groups of the Naga, linguistically related to the Chin, for instance believe that their ancestors cannot recognize them if they do not bear the ancient tattoo marks on their face and forehead (Saul, 2005). It is therefore possible that some of the Chin and other groups in the Mekong region followed a similar believe.

I met Khin Htay on one of my journeys through the Rakhine hinterland in Myanmar in 2005. It was five years after she had been tattooed. She granted me the privilege to take her portrait. She is the youngest and probably the last Chin woman on record that has received a traditional facial tattoo. Thinking of it, she is probably also the last girl of any hill tribe in the Mekong region that has undergone this ancient ritual.